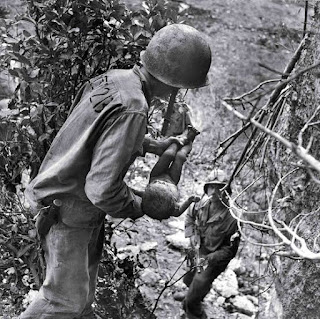

US Marine discovers a near-dead baby in a cave in the jungle of Saipan island, 1944

US Marine discovers a near-dead baby in a cave in the jungle of Saipan island, 1944

1944. A US Marine cradles the barely living body of a tiny infant, who was found facedown in a cave in the jungle of Saipan island, where native islanders had been hiding to escape the fighting between US and Japanese forces.

Photo by W. Eugene Smith.

In a photo that somehow comprises both tenderness and horror, an American Marine cradles a near-dead infant pulled from under a rock while troops cleared Japanese fighters and civilians from caves on Saipan in the summer of 1944.

The child was the only person found alive among hundreds of corpses in one cave. The battle for the Pacific island of Saipan during World War II is one of those well-remembered battles between Japan and America, one made worse by the mass suicide of local Japanese civilians who jumped off cliffs, fearful of capture by the Americans.

The Americans declared Saipan “secure” on July 9, 1944, after a battle that obliterated the 30,000-strong Japanese garrison and killed up to 12,000 of the local Chamorro and Carolinian islanders and Japanese civilian settlers on the island (Japanese settlers worked the island’s sugar cane fields).

This is what has been called “war without mercy” – battles supercharged by racial stereotypes about the enemy. Japanese soldiers hid out in the thick shrub on the island long after the battle ended, refusing to give up and attacking US troops stationed on the island. One sizeable group led by Captain Oba only surrendered in December 1945 when the war was long over.

1,000 Japanese civilians committed suicide in the last days of the battle by fears such as American mutilation of Japanese war dead. Some Japanese people living beside the cliff jumped from places that were later named Suicide Cliff and Banzai Cliff.

These would become part of the National Historic Landmark District as Landing Beaches; Aslito/Isley Field; & Marpi Point, Saipan Island, designated in 1985. Today the sites are a memorial and Japanese people visit to console the victim’s souls.

(Photo credit: Eugene Smith).

.jpg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment