The Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide

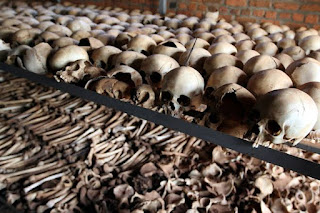

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu militias.

The most widely accepted scholarly estimates are around 500,000 to 662,000 Tutsi deaths.

In 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group composed mostly of Tutsi refugees, invaded northern Rwanda from their base in Uganda, initiating the Rwandan Civil War. Over the course of the next three years, neither side was able to gain a decisive advantage.

In an effort to bring the war to a peaceful end, the Rwandan government led by Hutu president, Juvénal Habyarimana[4] signed the Arusha Accords with the RPF on 4 August 1993.

The catalyst became Habyarimana's assassination on 6 April 1994, creating a power vacuum and ending peace accords. Genocidal killings began the following day when majority Hutu soldiers, police, and militia murdered key Tutsi and moderate Hutu military and political leaders.

The scale and brutality of the genocide caused shock worldwide, but no country intervened to forcefully stop the killings.[5] Most of the victims were killed in their own villages or towns, many by their neighbors and fellow villagers.

Hutu gangs searched out victims hiding in churches and school buildings. The militia murdered victims with machetes and rifles.

Sexual violence was rife, with an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 women raped during the genocide.

The RPF quickly resumed the civil war once the genocide started and captured all government territory, ending the genocide and forcing the government and génocidaires into Zaire.

The genocide had lasting and profound effects. In 1996, the RPF-led Rwandan government launched an offensive into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), home to exiled leaders of the former Rwandan government and many Hutu refugees, starting the First Congo War and killing an estimated 200,000 people.

Today, Rwanda has two public holidays to mourn the genocide, and "genocide ideology" and "divisionism" are criminal offences. Although the Constitution of Rwanda states that more than 1 million people perished in the genocide, the real number killed is likely lower.

Genocidal killings began the following day. Soldiers, police, and militia quickly executed key Tutsi and moderate Hutu military and political leaders who could have assumed control in the ensuing power vacuum.

Checkpoints and barricades were erected to screen all holders of the national ID card of Rwanda, which contained ethnic classifications. This enabled government forces to systematically identify and kill Tutsi.

They also recruited and pressured Hutu civilians to arm themselves with machetes, clubs, blunt objects, and other weapons and encouraged them to rape, maim, and kill their Tutsi neighbors and to destroy or steal their property.

The RPF restarted its offensive soon after Habyarimana's assassination. It rapidly seized control of the northern part of the country and captured Kigali about 100 days later in mid-July, bringing an end to the genocide.

During these events and in the aftermath, the United Nations (UN) and countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Belgium were criticized for their inaction and failure to strengthen the force and mandate of the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) peacekeepers.

In December 2017, media reported revelations that the government of France had allegedly supported the Hutu government after the genocide had begun.

The large scale killing of Tutsi on the grounds of ethnicity began within a few hours of Habyarimana's death. The crisis committee, headed by Théoneste Bagosora, took power in the country following Habyarimana's death, and was the principal authority coordinating the genocide.

Following the assassination of Habyarimana, Bagosora immediately began issuing orders to kill Tutsi, addressing groups of interahamwe in person in Kigali, and making telephone calls to leaders in the prefectures.

Other leading organisers on a national level were defence minister Augustin Bizimana; commander of the paratroopers Aloys Ntabakuze; and the head of the Presidential Guard, Protais Mpiranya.

Businessman Félicien Kabuga funded the RTLM and the Interahamwe, while Pascal Musabe and Joseph Nzirorera were responsible for coordinating the Interahamwe and Impuzamugambi militia activities nationally.

Military leaders in Gisenyi prefecture, the heartland of the akazu, were initially the most organized, convening a gathering of the Interahamwe and civilian Hutus; the commanders announced the president's death, blaming the RPF, and then ordered the crowd to "begin your work" and to "spare no one", including infants.

The killing spread to Ruhengeri, Kibuye, Kigali, Kibungo, Gikongoro and Cyangugu prefectures on 7 April; in each case, local officials, responding to orders from Kigali, spread rumours that the RPF had killed the president, followed by a command to kill Tutsi.

The Hutu population, which had been prepared and armed during the preceding months, and maintained the Rwandan tradition of obedience to authority, carried out the orders without question.

On the other hand, there are views that the genocide was not sudden, irresistible or uniformly orchestrated, but "a cascade of tipping points, and each tipping point was the outcome of local, intra-ethnic contests for dominance (among Hutu)".

The protracted struggles for supremacy in local communes meant that a more determined stance from the international community would likely have prevented the worst from happening.

In Kigali, the genocide was led by the Presidential Guard, the elite unit of the army. They were assisted by the Interahamwe and Impuzamugambi, who set up road blocks throughout the capital; each person passing the road block was required to show the national identity card, which included ethnicity, and any with Tutsi cards were killed immediately.

The militias also initiated searches of houses in the city, killing Tutsi and looting their property.

Tharcisse Renzaho, the prefect of Kigali-ville, played a leading role, touring the road blocks to ensure their effectiveness and using his position at the top of the Kigali provincial government to disseminate orders and dismiss officials who were not sufficiently active in the killings.

In rural areas, the local government hierarchy was also in most cases the chain of command for the execution of the genocide.

The prefect of each prefecture, acting on orders from Kigali, disseminated instructions to the commune leaders (bourgmestres), who in turn issued directions to the leaders of the sectors, cells and villages within their communes.

The majority of the actual killings in the countryside were carried out by ordinary civilians, under orders from the leaders. Tutsi and Hutu lived side by side in their villages, and families all knew each other, making it easy for Hutu to identify and target their Tutsi neighbours.

Gerard Prunier ascribes this mass complicity of the population to a combination of the "democratic majority" ideology, in which Hutu had been taught to regard Tutsi as dangerous enemies, the culture of unbending obedience to authority, and the duress factor—villagers who refused to carry out orders to kill were often branded as Tutsi sympathisers and they themselves killed.

There were few killings in the prefectures of Gitarama and Butare during the early phase, as the prefects of those areas were moderates opposed to the violence.

The genocide began in Gitarama after the interim government relocated to the prefecture on 12 April. Butare was ruled by the only Tutsi prefect in the country, Jean-Baptiste Habyalimana.

Habyalimana refused to authorise any killings in his territory, and for a while Butare became a sanctuary for Tutsi refugees from elsewhere in the country.

This lasted until 18 April, when the interim government dismissed him from his post and replaced him with government loyalist Sylvain Nsabimana.

The crisis committee appointed an interim government on 8 April; using the terms of the 1991 constitution instead of the Arusha Accords, the committee designated Théodore Sindikubwabo as interim president of Rwanda, while Jean Kambanda was the new prime minister.

All political parties were represented in the government, but most members were from the "Hutu Power" wings of their respective parties.

The interim government was sworn in on 9 April, but relocated from Kigali to Gitarama on 12 April, ostensibly fleeing RPF's advance on the capital.

The crisis committee was officially dissolved, but Bagosora and the senior officers remained the de facto rulers of the country. The government played its part in mobilising the population, giving the regime an air of legitimacy, but was effectively a puppet regime with no ability to halt the army or the Interahamwe's activities.

When Roméo Dallaire visited the government's headquarters a week after its formation, he found most officials at leisure, describing their activities as "sorting out the seating plan for a meeting that was not about to convene any time soon".

Death toll and timeline

During the remainder of April and early May, the Presidential Guard, gendarmerie and the youth militia, aided by local populations, continued killing at a very high rate.

The goal was to kill every Tutsi living in Rwanda and, with the exception of the advancing rebel RPF army, there was no opposition force to prevent or slow the killings.

The domestic opposition had already been eliminated, and UNAMIR were expressly forbidden to use force except in self-defence.

In rural areas, where Tutsi and Hutu lived side by side and families knew each other, it was easy for Hutu to identify and target their Tutsi neighbours.

In urban areas, where residents were more anonymous, identification was facilitated using road blocks manned by military and interahamwe; each person passing the road block was required to show the national identity card, which included ethnicity, and any with Tutsi cards were killed immediately.

Many Hutu were also killed for a variety of reasons, including alleged sympathy for the moderate opposition parties, being a journalist or simply having a "Tutsi appearance".

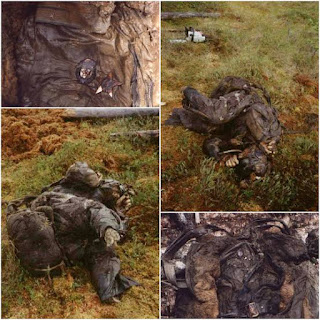

Thousands of bodies were dumped into the Kagera River, which ran along the northern border between Rwanda and Uganda and flowed into Lake Victoria.

This disposal of bodies caused significant damage to the Ugandan fishing industry, as consumers refused to buy fish caught in Lake Victoria for fear that they were tainted by decomposing corpses.

The Ugandan government responded by dispatching teams to retrieve the bodies from the Kagera River before they entered the lake.

The RPF was making slow but steady gains in the north and east of the country, ending the killings in each area occupied.

The genocide was effectively ended during April in areas of Ruhengeri, Byumba, Kibungo and Kigali prefectures.The killings ceased during April in the akazu heartlands of western Ruhengeri and Gisenyi, as almost every Tutsi had been eliminated.

Large numbers of Hutu in the RPF-conquered areas fled, fearing retribution for the genocide; 500,000 Kibungo residents walked over the bridge at Rusumo Falls into Tanzania in a few days at the end of April, and were accommodated in United Nations camps effectively controlled by ousted leaders of the Hutu regime, with the former prefect of Kibungo prefecture in overall control.

In the remaining prefectures, killings continued throughout May and June, although they became increasingly low-key and sporadic; most Tutsi were already dead, and the interim government wished to rein in the growing anarchy and engage the population in fighting the RPF.

On 23 June, around 2,500 soldiers entered southwestern Rwanda as part of the French-led United Nations Opération Turquoise. This was intended as a humanitarian mission, but the soldiers were not able to save significant numbers of lives.

The genocidal authorities were overtly welcoming of the French, displaying the French flag on their own vehicles, but killing Tutsi who came out of hiding seeking protection.

In July, the RPF completed their conquest of the country, with the exception of the zone occupied by Operation Turquoise. The RPF took Kigali on 4 July, and Gisenyi and the rest of the northwest on 18 July.

The genocide was over, but as had occurred in Kibungo, the Hutu population fled en masse across the border, this time into Zaire, with Bagosora and the other leaders accompanying them.

The succeeding RPF government claims that 1,074,017 people were killed in the genocide, 94% of whom were Tutsi.

In contrast, Human Rights Watch, following on-the-ground research, estimated the casualties at 507,000 people. According to a 2020 symposium of the Journal of Genocide Research, the official figure is not credible as it overestimates the number of Tutsi in Rwanda prior to the genocide.

Using different methodologies, the scholars in the symposium estimated 500,000 to 600,000 deaths in the genocide—around two-thirds of the Tutsis in Rwanda at the time.

Thousands of widows, many of whom were subjected to rape, became HIV-positive. There were about 400,000 orphans and nearly 85,000 of them were forced to become heads of families.

An estimated 2,000,000 Rwandans, mostly Hutu, were displaced and became refugees. Additionally, 30% of the Pygmy Batwa were killed.

On 9 April, UN observers witnessed the massacre of children at a Polish church in Gikondo. The same day, 1,000 heavily armed and well trained European troops arrived to escort European civilian personnel out of the country.

The troops did not stay to assist UNAMIR

Media coverage picked up on the 9th, as The Washington Post reported the execution of Rwandan employees of relief agencies in front of their expatriate colleagues.

Butare prefecture was an exception to the local violence. Jean-Baptiste Habyalimana was the only Tutsi prefect, and the prefecture was the only one dominated by an opposition party.

Opposing the genocide, Habyalimana was able to keep relative calm in the prefecture, until he was deposed by the extremist Sylvain Nsabimana.

Finding the population of Butare resistant to murdering their citizens, the government flew in militia from Kigali by helicopter, and they readily killed the Tutsi.

Most of the victims were killed in their own villages or in towns, often by their neighbors and fellow villagers. The militia typically murdered victims with machetes, although some army units used rifles.

The Hutu gangs searched out victims hiding in churches and school buildings and massacred them.

Local officials and government-sponsored radio incited ordinary citizens to kill their neighbors, and those who refused to kill were often murdered on the spot: "Either you took part in the massacres or you were massacred yourself."

One such massacre occurred at Nyarubuye. On 12 April, more than 1,500 Tutsis sought refuge in a Catholic church in Nyange, then in Kivumu commune.

Local Interahamwe, acting in concert with the authorities, used bulldozers to knock down the church building. The militia used machetes and rifles to kill every person who tried to escape.

Local priest Athanase Seromba was later found guilty and sentenced to life in prison by the ICTR for his role in the demolition of his church; he was convicted of the crime of genocide and crimes against humanity.

In another case, thousands sought refuge in the Official Technical School (École technique officielle) in Kigali where Belgian UNAMIR soldiers were stationed. On 11 April, the Belgian soldiers withdrew, and Rwandan armed forces and militia killed all the Tutsi.

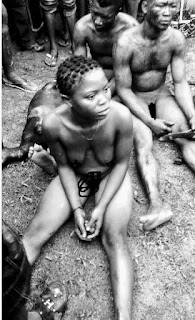

Sexual violence

Rape was used as a tool by the Interahamwe, the chief perpetrators, to separate the consciously heterogeneous population and to drastically exhaust the opposing group. The use of propaganda played an important role in both the genocide and the gender specific violence.

The Hutu propaganda depicted Tutsi women as "a sexually seductive 'fifth column' in league with the Hutus' enemies".

The exceptional brutality of the sexual violence, as well as the complicity of Hutu women in the attacks, suggests that the use of propaganda had been effective in the exploitation of gendered needs which had mobilized both females and males to participate.

Soldiers of the Army for the Liberation of Rwanda and the Rwandan Defence Forces, including the Presidential Guard, and civilians also committed rape against mostly Tutsi women. Although Tutsi women were the main targets, moderate Hutu women were also raped.

Along with the Hutu moderates, Hutu women who were married to or who hid Tutsis were also targeted. In his 1996 report on Rwanda, the UN Special Rapporteur Rene Degni-Segui stated, "Rape was the rule and its absence was the exception."

He also noted, "Rape was systematic and was used as a weapon." With this thought and using methods of force and threat, the genocidaires forced others to stand by during rapes.

A testimonial by a woman of the name Marie Louise Niyobuhungiro recalled seeing local peoples, other generals and Hutu men watching her get raped about five times a day. Even when she was kept under watch of a woman, the woman would give no sympathy or help and furthermore forced her to farm land in between rapes.

Many of the survivors became infected with HIV from the HIV-infected men recruited by the genocidaires. During the conflict, Hutu extremists released hundreds of patients suffering from AIDS from hospitals, and formed them into "rape squads".

The intent was to infect and cause a "slow, inexorable death" for their future Tutsi rape victims. Tutsi women were also targeted with the intent of destroying their reproductive capabilities.

Sexual mutilation sometimes occurred after the rape and included mutilation of the vagina with machetes, knives, sharpened sticks, boiling water, and acid. Men were also the victims of sexual violation, including public mutilation of the genitals.

Some experts have estimated that between 250,000 and 500,000 women were raped during the genocide.

Citations

Meierhenrich, Jens (2020). "How Many Victims Were There in the Rwandan Genocide? A Statistical Debate". Journal of Genocide Research. 22 (1): 72–82. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1709611. S2CID 213046710. The lower bound for Tutsi deaths is 491,000 (McDoom), see page 75 mention

"Commemoration of International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda – Message of the UNOV/ UNODC Director-General/ Executive Director". United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

Guichaoua, André (2 January 2020). "Counting the Rwandan Victims of War and Genocide: Concluding Reflections". Journal of Genocide Research. 22 (1): 125–141.

doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1703329. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 213471539.

Sullivan, Ronald (7 April 1994). "Juvenal Habyarimana, 57, Ruled Rwanda for 21 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment