The Korean War Hasn't Officially Ended. One Reason: POWs

The Korean War Hasn't Officially Ended. One Reason: POWs

Prisoner exchanges were critical to a ceasefire in the Korean War—but a peace treaty was never signed.

Shot haven’t been fired in the Korean War for nearly 70 years—but that doesn’t mean it’s over. Officially, the Korean War never technically ended.

Although the Korean Armistice Agreement brought an end to the hostilities that killed 2.5 million people on July 27, 1953, that ceasefire never gave way to a peace treaty. At the time, South Korea’s president refused to accept the division of Korea.

A peace treaty between North Korea and South Korea today would be anything but symbolic, however: It could usher in real change in both countries. But should serious peace talks ever occur, they might run into a major obstacle: prisoners of war.

That might sound eerily familiar to anyone familiar with how the Korean War wound down. In 1953, prisoners of war became a thorny sticking point between both sides, threatening any chance of peace and contributing to an ongoing stalemate as millions died.

Yet the end of the war hinged on successfully negotiating the fate of POWs on both sides. Those negotiations resulted in two massive prisoner exchanges that marked the war’s end.

The exchanges took place in two waves—Operation Little Switch, in which sick and wounded prisoners changed hands, and Operation Big Switch, the final push to exchange all remaining prisoners between sides.

Fraught with controversy and risk, these prisoner of war exchanges were among the tensest moments of a war marked by catastrophe. And they still affect the chance of peace across the Korean peninsula.

A messy proxy war

The Korean War was a military and diplomatic disaster from its very beginning. The war was technically between North Korea and South Korea, but it played out against a backdrop of Cold War tensions.

After North Korean forces invaded South Korea in June 1950, the United States led United Nations forces to defend South Korea. North Korea was advised, armed and trained by the USSR, and China came to its aid with over 2 million soldiers—the first time the Chinese military had fought on a large scale outside of China. As a result, the conflict was a proxy for the Cold War.

That chill marked the war from the start. Troops quickly became entrenched after a failed attempt to conclude the war deep inside North Korea. For two years, both sides fought around the 38th parallel, achieving a complete stalemate that was matched by a stalemate at the negotiating table between the parties, who could not agree on how to cease the war.

Meanwhile, casualties and deaths piled up. Nearly 37,000 Americans were killed during the war. At least 1 million South Korean civilians were killed, and 7,000 South Korean military members died. In North Korea, 406,000 soldiers died, and 600,000 civilians were killed. Another 600,000 Chinese military members died in the war, too.

Among the deaths were those of prisoners of war who faced torture and starvation in North Korea. Conditions were especially hard for South Koreans who were captured by North Korea and China. Viewed as traitorous defectors, they were treated harshly. Though POWs detained by the United States died, too, they were more likely to die of infectious diseases like dysentery.

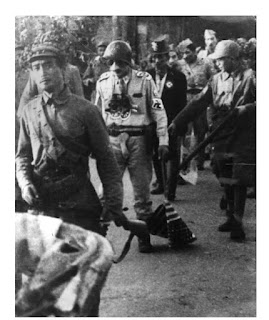

|

| An exchange of prisoners between the United Nations and the Communists at Panmunjom, Korea in August 1953. Central Press/Getty Images |

How POW exchanges became a sticking point in peace negotiations

During the war, the United States and its allies captured tens of thousands of Communist soldiers. Many of those POWs claimed they had been coerced into fighting for China and North Korea and said they did not want to return to their home countries once they were exchanged.

This presented a serious stumbling block to peace negotiations between the parties. North Korea and China insisted that their POWs be repatriated; the United States and South Korea refused on humanitarian grounds.

Finally, as the military stalemate dragged on, North Korea and China relented, conceding to American demands to let prisoners of war either return or be granted asylum with their captors as long as a neutral UN commission handled POWs who didn’t want to return.

The newly empowered Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission, led by India, sprang into action. The first priority was sick and injured POWs, and in April 1953, Operation Little Switch began.

The Communists traded 684 United Nations troops for over 5,000 North Koreans, 1,000 Chinese and about 500 civilians.

However, United States officials complained that the Communists were construing “sick and wounded” so narrowly that they had not released the proper number of POWs, and squabbling over the best way to exchange the prisoners continued.

The next phase was the trade of the much larger number of POWs who were not deemed sick or wounded. By then, the terms of the armistice had mostly been hashed out. On August 5, 1953, Operation Big Switch began.

Over 75,000 Communist prisoners were returned to North Korea and China, which handed over 12,722 prisoners from the United Nations Command. Over 22,000 Communist soldiers decided to seek asylum rather than return to their home countries; 88 defected to India, instead. And a handful of Americans refused to be repatriated.

It was an ambitious exchange, and not without major crises. The main one came in the form of Syngman Rhee, then president of South Korea. He did not want the war to end at all without the reunification of Korea, and Rhee threatened to mobilize his own soldiers against their UN allies during prisoner returns.

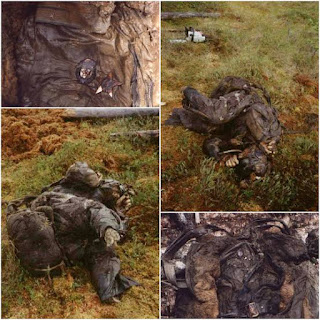

Another problem was the condition of the POWs, many of whom had been subjected to torture and brainwashing while in Communist custody.

And then there were the POWs who were not returned at all. About 80,000 South Koreans were in North Korea when a ceasefire ended the war. Most are thought to have been put to work as laborers, “re-educated,” and integrated into North Korean society.

In 2010, South Korea estimated that 560 were still alive. Their ordeals in repressive North Korea were unknown until a small group of defectors told their stories.

An armistice without a peace treaty

The United States withdrew from the Korean War in 1953, after a ceasefire and armistice agreement brought the fighting to an end. But that didn’t mean an end to the war itself.

Nearly 70 years after it started, the Korean War is technically still in progress. China, North Korea and the United States both signed on to the armistice, but South Korea, intent on reunification, did not.

A failed 1954 peace conference in Geneva, Switzerland yielded no peace treaty. Since the armistice is a military agreement and not a treaty between nations, the war still technically continues.

So do questions about what happened to the POWs North Korea never returned. Both South Korea and non-governmental organizations have asked for their repatriation, but North Korea refuses to address the issue.

Meanwhile, the status of the few who are presumed living is unknown. About 80 former POWs did escape North Korea.

But though the prisoner exchanges of 1953 helped bring an end to the military portion of the Korean War, it didn’t put an end to questions about the remaining POWs’ fates.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment