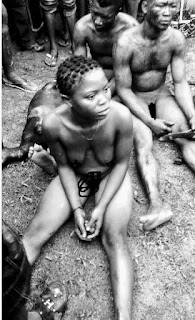

The grief of Senad Medanovic, a Bosnian who returned to his newly liberated village and learned that his family had been massacred by the Serbs - 1995

The grief of Senad Medanovic, a Bosnian who returned to his newly liberated village and learned that his family had been massacred by the Serbs - 1995

KRASULJE, Bosnia-Herzegovina — When he fled the Serbian takeover of his town near here three years ago, Fudo Kestic, a 24-year-old Bosnian soldier, left behind a mother and sister. Today, having returned triumphant with the government forces that regained the town a few days ago, he faces the hard reality that his family is probably dead.

“I knew what the Serbs were doing, so I had lost hope,” Kestic said Monday, after he found his home in ruins. “My mother and sister were there, and now they’re not.”

As the Bosnian government reoccupies land that has been under tight Serbian control since war began in the spring of 1992, a new phase of accounting, reckoning and discovery is about to open. Muslim Bosnians are returning to ravaged villages in search of homes and the truth; the full extent of campaigns of “ethnic cleansing” that uprooted entire populations is once again coming into focus.

And reports of mass graves are surfacing, as are captured documents that may explain the whereabouts of the many missing.

Here in Krasulje, Kestic and a group of soldiers from the government’s vaunted 5th Corps stood guard over the road that runs from Kestic’s hometown, Kljuc, to the front line and to one of at least three sites in this area that officials and survivors say contain mass graves.

“When we fled Kljuc, it was dusk and smelled of smoke,” Kestic recalled. “All we could hear were the women and children crying and the songs of drunken Chetniks [Serbs]. . . .

“And when we came back, all we could think of was to keep marching forward. We knew the people we were fighting against were the same ones who had torched our villages. At each step, everyone had a picture in his mind of what had happened before.”

The Krasulje grave site could not be reached Monday because, Kestic and the other soldiers said, it lies too close to the fighting. But excavation has started or is being planned for two other sites in the thick-forested hills above Kljuc: Crvena Zemlja and Prhovo.

Bosnian Prime Minister Haris Silajdzic over the weekend claimed that 540 people were buried around Kljuc, primarily Muslim men and women killed in the early months of the war.

U.N. spokesman Chris Gunness said Monday in Zagreb, the Croatian capital, that Bosnian authorities have told U.N. military observers that there are 40 possible mass grave sites in the huge swath of territory retaken by government forces in the past few weeks.

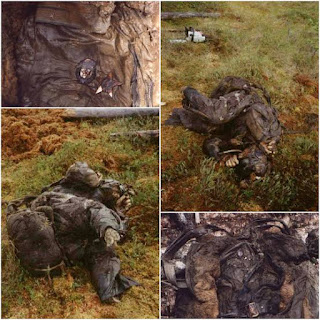

At Crvena Zemlja, or red earth, a climb down a steep, muddy hill off a dirt-and-rock road on Monday revealed a large pit from which parts of one clothed skeleton protruded. A skull and two femurs were clearly visible. The hillside is dotted with caves.

Preliminary digging by soldiers had reportedly yielded a few skulls and other bones.

At Prhovo, a grassy spot marks the burial of most of the Muslim village’s residents, according to a survivor who took reporters there. The man, Senad Medanovic, told reporters that 70 people, including three brothers and a sister, were killed in June of 1992 and their bodies bulldozed into the ground.

All sides committed atrocities in this war, but by most accounts the months of 1992 saw an especially brutal campaign by Bosnian Serb rebels to rid territory they took of non-Serbs. They rounded up people in camps and have been accused of widespread murder, rape and expulsions, often followed by the burning and razing of Muslim and Croatian homes.

Kamel Komic, a police commander in another newly recaptured town, Jasenica, said returning villagers have begun to tell authorities of the horrors they witnessed and have led them to sites of possible massacres.

Also, Komic said, in Jasenica and several other towns, the Serbian authorities fled in such a rush that they left behind documents that are expected to shed light on what happened to many victims.

For example, he said, government troops found letters from Jasenica municipal officials identifying Muslim prisoners in custody. Those same prisoners later turned up dead and were offered in body swaps between the two sides.

Kestic, the soldier who returned to Kljuc, believes his mother and sister were taken to one of the camps, where they probably perished. He fled the town in May, 1992, with 149 other fighters. In a desperate bid for freedom, the Muslim fighters captured two Serbian majors and 60 Serbian soldiers as hostages, with whom they bartered their escape.

The women and children of Kljuc were left behind, apparently because it was thought they would be safe. But as the men fled over Mt. Grmec, they heard the cries.

“I remember a child crying, ‘Mama, Mama,’ ” Kestic said. “It is still hard to talk about this.”

The road from the newly retaken Kljuc to Bihac, a government stronghold, was crowded Monday with tractors and horse carts piled high with hay, cattle and furniture looted from abandoned Serbian farms by Muslim villagers and refugees.

One slow-moving wagon hauled four sofas, with an elderly peasant woman perched on top.

The road is also one of death and the debris of war. In the government offensive launched two weeks ago, tank battles were evidently fought in spots where it curves through bucolic hillside pastures and fields. On Monday, cars caught in flight lay splayed to one side or the other; blankets and cooking utensils were hurled about.

Six corpses, including those of an elderly couple, were still visible along one 12-mile stretch, along with scores of dead sheep and other livestock.

The battlefields of northwestern Bosnia, following major gains made by the government army and its Croatian allies, remained very much in flux Monday. Fighting continued, and the Serbs claimed that a counteroffensive had inflicted heavy casualties on Bosnian troops.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment