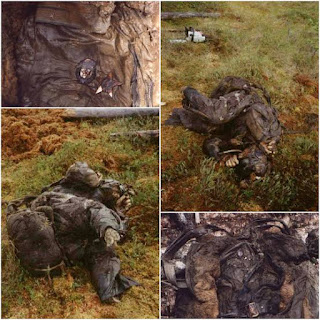

The Bataan Death March.

.jpeg) |

| The brutal Bataan march |

The Bataan Death March.

The Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of between 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war from Saysain Point, Bagac, Bataan and Mariveles to Camp O'Donnell, Capas, Tarlac, via San Fernando, Pampanga, the prisoners being forced to march despite many dying on the journey.

The transfer began on April 9, 1942, after the three-month Battle of Bataan in the Philippines during World War II.

The total distance marched from Mariveles to San Fernando and from the Capas Train Station to various camps, the route was 65 miles long.

Sources also report widely differing prisoner of war casualties prior to reaching Camp O'Donnell: from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march.

If an American soldier was caught on the ground or fell they would be instantly shot. As of now all the reported American soldiers that passed now have a grave stone honoring those who died.

The march was characterized by severe physical abuse and wanton killings. After the war, the Japanese commander, General Masaharu Homma and two of his officers, Major General Yoshitaka Kawane and Colonel Kurataro Hirano, were tried by United States military commissions for war crimes and sentenced to death on charges of failing to prevent their subordinates from committing war crimes. Homma was executed in 1946, while Kawane and Hirano were executed in 1949.

Following the surrender of Bataan on April 9, 1942, to the Imperial Japanese Army, prisoners were massed in the towns of Mariveles and Bagac. They were ordered to turn over their possessions. American Lieutenant Kermit Lay recounted how this was done:

They pulled us off into a rice paddy and began shaking us down. There [were] about a hundred of us so it took time to get to all of us. Everyone had pulled their pockets wrong side out and laid all their things out in front.

They were taking jewelry and doing a lot of slapping. I laid out my New Testament. ... After the shakedown, the Japs took an officer and two enlisted men behind a rice shack and shot them. The men who had been next to them said they had Japanese souvenirs and money.

Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as their captors would assume it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers.

"One of the POWs had a ring on and the Japanese guard attempted to get the ring off," said one U.S. prisoner. "He couldn't get it off and he took a machete and cut the man's wrist off and when he did that, of course the man was bleeding profusely.

[I tried to help him] but when I looked back I saw a Japanese guard sticking a bayonet through his stomach."

Prisoners started out from Mariveles on April 10, and Bagac on April 11, converging in Pilar, Bataan, and heading north to the San Fernando railhead.

At the beginning, there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as the sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting personal possessions to be kept.

This, however, was quickly followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men's teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suffered in the battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his "captives" (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs).

The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel Masanobu Tsuji[10]—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and NCOs under his supervision were summarily executed in the Pantingan River massacre after they had surrendered.

Tsuji—acting against General Homma's wishes that the prisoners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American "captives". Although some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.

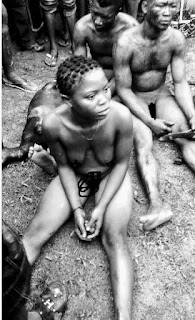

During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died.

[self-published source] They were subjected to severe physical abuse, including beatings and torture. On the march, the "sun treatment" was a common form of torture.

Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight without helmets or other head coverings. Anyone who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water.

Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue, and "cleanup crews" put to death those too weak to continue, though some trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to go on. Some marchers were randomly stabbed with bayonets or beaten.

Once the surviving prisoners arrived in Balanga, the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused dysentery and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies.

Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prisoners were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Capas, in 43 °C (110 °F) heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners. According to Staff Sergeant Alf Larson:

The train consisted of six or seven World War I-era boxcars. ... They packed us in the cars like sardines, so tight you couldn't sit down. Then they shut the door. If you passed out, you couldn't fall down. If someone had to go to the toilet, you went right there where you were.

It was close to summer and the weather was hot and humid, hotter than Billy Blazes! We were on the train from early morning to late afternoon without getting out. People died in the railroad cars.

Upon arrival at the Capas train station, they were forced to walk the final 9 miles (14 km) to Camp O'Donnell.[14] Even after arriving at Camp O'Donnell, the survivors of the march continued to die at rates of up to several hundred per day, which amounted to a death toll of as many as 20,000 Americans and Filipinos.

Most of the dead were buried in mass graves that the Japanese had dug behind the barbed wire surrounding the compound. Of the estimated 80,000 POWs at the march, only 54,000 made it to Camp O'Donnell.

The total distance of the march from Mariveles to San Fernando and from Capas to Camp O'Donnell (which ultimately became the U.S. Naval Radio Transmitter Facility in Capas, Tarlac; 1962–1989) is variously reported by differing sources as between 60 and 69.6 miles (96.6 and 112.0 km).

The Death March was later judged by an Allied military commission to be a Japanese war crime.

Casualty estimates

The only serious attempt[according to whom?] to calculate the number of deaths during the march on the basis of evidence is that of Stanley L. Falk.

He takes the number of American and Filipino troops known to have been present in Bataan at the start of April, subtracts the number known to have escaped to Corregidor and the number known to have remained in the hospital at Bataan.

He makes a conservative estimate of the number killed in the final days of fighting and of the number who fled into the jungle rather than surrender to the Japanese. On this basis he suggests 600 to 650 American deaths and 5,000 to 10,000 Filipino deaths.

Other sources report death numbers ranging from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march.

Citations

*History (November 9, 2009). "Bataan Death March". history.com. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

*Morton, Louis (1953). The Fall of the Philippines. US Army Center of Military History.

*Murphy, Kevin C. (2014). Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-7864-9681-5.

*Esconde, Ernie B. (April 9, 2012). "WW2 historical markers remind Pinoys of Bataan's role on Day of Valor". GMA Network. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment