Serial killer Dean Corll

Serial killer Dean Corll.

Around 8:30 a.m. on August 8, 1973, Wednesday morning, the Pasadena, TX, police department got a telephone call from a hysterical Wayne Henley.

Patrolman A.B. Jamison raced over to the address, 2020 Lamar Drive, a green and white frame house. Three teenagers, two boys and a girl stood in front of the house.One of the boys,Wayne Henley, came forward and told the police motioned the cop inside where Corll's body lay on the floor.

Corll had been a large muscular man over six feet tall and weighing approximately 200 pounds. His dark brown hair, graying at the temples, was styled in little waves. His identification showed his name as Dean Arnold Corll, a 33-year-old electrician for Houston Power and Light.

Detectives had arrived to examine the sparsely furnished crime scene one of the more interesting ones they had witnessed in some time. Corll had been shot six times with bullets lodging in the chest, shoulder and head.

In the bedroom plastic sheeting covered the carpet to protect it from dripping blood. The bedding on the one single bed was all tangled and disarrayed. Most sinister was the large thick plywood board with several sets of handcuffs, ropes and cords attached to it. On the floor was a bayonet-like knife, a huge dildo, binding tape, glass tubes and petroleum jelly..

Corll’s body was taken to the morgue, while the three teenagers were taken to the police station for questioning. Henley told police that Corll was a homosexual and pedophile that paid him to procure victims, which Corll later murdered and buried in a boat shed.

Once Corlls parents arrived a different story emerged. They said that the story the teenagers had told police was a lie and that Dean had never been a homosexual or a violent person.

In fact, Dean loved kids and had always been generous to young people. These teenagers, had taken advantage of their son's hospitality and then, crazed by drugs, had murdered him in his own home.

A teenaged homosexual who called himself "Guy" spoke with detectives and stated that Corll made a sexual pass at him in a public men's room. "I just wasn't interested at all," Guy said. "We became extremely close friends." He said that Corll was extremely gentle and kind to him, but he had in his house a bedroom that was off limits to Guy. "I'll never take you in there," Corll told him.

Guy claimed that Corll was very critical of openly gay bars and bathhouses. There was a barrier that Dean had set up between himself and an overtly gay lifestyle.

Dean Corll was born December 24, 1939, in Fort Wayne, Indiana to Arnold & Mary Corll. The marriage of Arnold and Mary was not a happy one and when Dean was six, the parents divorced, leaving Mary to raise Dean and a second son, Stanley.

At this time in his young life, Dean was diagnosed with a heart murmur, which put a damper on any athletic endeavors. Dean studied music instead and became a trombone player in his high school band. His grades were middle-of-the-road in school, but he was always neat and well behaved.

In the late 1950s, Mary started making pecan candies. Dean helped gather pecans and delivered the candy for his mother. Mary had set up a candy production facility in her home and turned her garage into a candy store. Dean became second in command in his mother's candy business and lived in an apartment over the garage.

He made candy at night, while during the day he brought in a regular salary with Houston Lighting and Power. The candy company moved to West 22nd street near Helms Elementary School in the Heights area of Houston. Dean invited all the local kids in for free candy and became known as the Candy Man. After a few short years the candy factory closed.

The first victims

A huge tragedy began quietly in The Heights on May 29, 1971. 13-year-old David Hilligiest and his 16-year-old friend Gregory Malley Winkle did not come home from a trip to the neighborhood swimming pool. That night, Mrs. Winkel got a very strange phone call from Malley just before midnight. When she asked where he was, there was a long pause.

"We're in Freeport, Mother," her son told her. "I called to let you know where I was."

He told her he was just with a bunch of boys swimming, but that they would bring him home later. The next day, she heard that Malley and David had been seen in a white van, but none of his friends knew what had happened to the boys.

A few months later, on August 17, 17-year-old Ruben Watson was given some money by his grandmother to go to a movie and told his mother he would see her when she got home from work at 7:30 p.m., but he never made it.

Ten months later on March 24, 1972, Rhonda's boyfriend, Frank Aguirre, finished his shift at the Long John Silver's restaurant and told his mother he would be home by 10 p.m. He also called Rhonda and said he was on his way to her house. She waited outside, but he didn't come.

She walked down to the corner and noticed that Frank's car was gone. Rhonda went back home and continued to wait, but he never showed up. Instead, he disappeared. Wayne Henley came looking for Rhonda. He pulled her aside and told her to stop thinking that Frank would ever return.

Wayne told her that Frank had gotten into some trouble with Mafia-type people and they had taken him. Wayne told her that he couldn't say any more than that because he was afraid of those people and he was putting himself in danger for speaking to her about Frank.

Then Wayne left the restaurant and got into Dean Corll's van.

On May 21, 1972, 16-year-old Johnny Delome vanished along with his friend 17-year-old Billy Baulch. The police were no help, so the Baulches tried to run down clues on their own. As they trawled through suspicious incidents in their son's past, they remembered David Brooks had given Billy some dope, which they reported to the police.

They also recalled Dean Corll, Brooks' companion, who used to have Billy and other neighborhood kids in his home on a continuous basis.

When Mrs. Baulch asked Billy what he and the other boys do for hours at the home of Dean Corll, Billy told her:

We play the stereo and watch TV,. The Baulches went looking for the candy man. When they found him, Dean Corll was polite and respectful, but he said he had no idea where Billy or Johnny had gone.

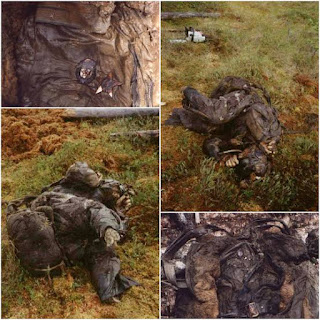

Wayne took investigators to Deans boat shed Wayne Henley claimed that Corll had murdered several boys and buried three of them in a boat shed several miles south of Houston.

In late afternoon, he guided police and some prison "trusties" to a street named "Silver Bell" and a marina with a business called "Southwest Boat Storage." Dean Corll's stall was Number 11.

The stall had no windows, and the officers moved slowly as they accustomed their eyes to the gloom of the deep interior. Two faded carpets covered the earthen floor, stretching from the entrance back 12 feet. One was green, the other blue. Inside the doors on the left stood a huge, empty appliance carton.

A half-stripped car body, covered by a sheet of canvas, sat in the right-rear area of the stall...behind the barrel in the corner was a plastic bag and inside this was an empty lime bag. n the blazing August heat, the "trusties" that police had brought along for the digging, reached a layer of lime.

The sweat poured off the prisoners as they dug through the white layer of lime. A few inches later, detectives saw some plastic sheet, which held the naked body of a boy about 13. Below the first body was a skeleton.

Then when they dug to the right of the first grave, the bodies of two additional teenagers were found. One had been shot and the other strangled. By midnight, the bodies of eight victims had been recovered.

Jack Olsen captured the horror of the police in a phrase: "They had all seen death, but none had encountered the wholesale transfiguration of rollicking boys into reeking sacks of carrion.

By the end of the first day, the Hilligiests and Mrs. Winkle and several other parents understood why they had never seen their boys alive again. By the end of the second day of the investigation, the body count had risen to 17.

Both Henley and Brooks were told to make a list of every boy that they remembered as a victim. Henley, who never stopped talking, told police that several boys were buried near Lake Sam Rayburn and on the High Island beach. A trip was planned immediately to those sites.

Several bodies were discovered fairly soon, but since it was late in the day, further digging had to wait until the following day.

Over the coming days, 17 bodies were found in the boat shed and before the investigation was completed, the bodies of 27 boys had been unearthed making the serial murder case the largest in U.S. history, beating the existing record of Juan Corona's 25 victims.

Wayne Henley delivered justice to Dean Corll on August 8, 1973, when he shot him in self-defense. Wayne and David Brooks had been planning to kill Corll because they were afraid of him and afraid that he had gone crazy.

They had always considered themselves potential victims and worried that they might not see it coming fast enough to escape. In 1974, Wayne Henley was convicted of murder in the deaths of six boys and was sentenced to six consecutive 99-year terms.

In 1975, David Brooks was convicted of murder in the death of one 15-year-old boy and was sentenced to life.

Pictures of

Dean Corll

Dean Corlls house

Wayne Henley and David Brooks

Digging up the boat shed PIC 5: Early Victims.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment